Just another day in Israel, the only democracy in the Middle East.

It is of course possible to criticize Israel without being antisemitic. In fact, no one is more openly critical of the Israeli government than the citizens of Israel (a vibrant democracy where freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of religion, and freedom of the press are energetically exercised by its citizens).

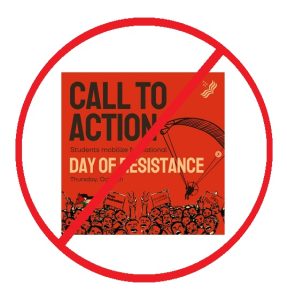

But much of what is today presented as merely, and innocently, “criticism of Israel” is, in reality, deeply and profoundly antisemitic. Sometimes this is obvious, as in the case of groups like “Students for Justice in Palestine” (SJP) who have openly expressed their sympathy for Hamas and their approval of the October 7 pogrom. Or the case of “feminist” theorist Judith Butler, who embraces Hamas as a “progressive” group that is part of the “global left”!

But most cases are not quite so straightforward as it is with Judith Butler and the SJP, who, for whatever reason, don’t even try to hide their antisemitism. Part of the problem is that antisemitism is a systemic phenomenon that can influence people who honestly believe that the things they say and do are not antisemitic. One way of investigating such systemic and possibly unconscious antisemitic behavior and speech is by looking for double standards. Indeed, it is well known that the existence of double standards can be used as evidence for racism, sexism, and other forms of bigotry.

For example, since 2015 the Stanford Open Policing Project has collected and standardized over 200 million reports of police traffic stops and searches from across the United States. As part of their findings, they report that “we find that police require less suspicion to search Black and Hispanic drivers than white drivers. This double standard is evidence of discrimination.”

When double standards are at work this means that the same behavior is treated differently depending on who is doing it. Black drivers and white drivers are treated differently not based on differences in how they drive, but simply based on race.

Detecting double standards is especially important when dealing with forms of bigotry that are considered socially unacceptable, and, therefore, unlikely to be expressed openly. If police officers are simply asked, “Are you racist?”, they will obviously insist that they are not. But despite such protestations, statistically it can be shown that Black drivers are subjected to a racially motivated double standard.

Investigating double standards is also a way of shining a light on otherwise hidden antisemitism.

Israel is the world’s only Jewish state. Therefore when Israel is singled out and subjected to criticism in a way that is clearly different from how other states are treated, this can be evidence of antisemitism. Criticism of Israel that clearly evinces a double standard might not always be considered sufficient evidence, on its own, to conclude that those making the criticism are acting out of antisemitism. However, in the context of a worldwide upsurge of antisemitism, those who single out Israel for criticism in a way that is obviously not consistently applied to other countries owe us some explanation for this, and unless a convincing alternative explanation can be provided, then it is reasonable to consider such critics with suspicion, and to look for further evidence. If you see a police officer pulling over a Black motorist, it does not automatically mean that there is racism afoot. But it is reasonable to become curious about how often that officer pulls over Black drivers as opposed to white drivers.

In extreme cases, where the double standard goes so far as to cast Israel as the single greatest source of evil in the world, then this alone is not only clear evidence of antisemitism, it is very close to being explicitly antisemitic. In fact, the classical form of early 20th century antisemitism focused on blaming the Jews for all the world’s problems. If one simply replaces “the Jews” with “the Jewish state” then one has this extreme form of an obviously antisemitic double standard now applied to the Jewish state of Israel.

Directly related to the inherent antisemitism of depicting the Jewish state as the main cause of the world’s worst problems is the “double standard of salience”. Two scholars who study antisemitism, Sina Arnold and Blair Taylor, wrote the following about this double standard, and in particular how it manifests among leftist anti-Zionists:

The double standard of salience translates into a political context where the left assigns vastly more attention and importance to the issue of Israel/Palestine than any other conflict in the world today. Israel is one of the few issues that unites a typically fractious left. This one conflict is so central to the U.S. left’s self-understanding that that it is often a highly visible element even in demonstrations for completely unrelated topics like climate change, police brutality, or gay rights. This ideological omnipresence suggests that the left views Israel as both a unifying factor as well as a political lynchpin upon which various other forms of oppression rest. Yet at the same time, various other occupations, civil wars, and violent conflicts receive little or no attention from the left…. [Antisemitism and the Left: Confronting an Invisible Racism]

One could hardly imagine a more glaring example of the double standard of salience than Bhikkhu Bodhi’s article Israel’s Gaza Campaign Is the Gravest Moral Crisis of Our Time which appeared on the Common Dreams website on Feb 12, 2024 (link).

In that article, Bhikkhu Bodhi does acknowledge in passing that that there are other possible contenders for the title of “Gravest Moral Crisis of Our Time”:

Given the many instances of sheer inhumanity unfolding over just two decades—in Iraq, Syria, Tigray, Myanmar, and Ukraine—why should I highlight Gaza as the major moral calamity of our time? I will lay down five reasons this is the case.

However, in the remainder of Bodhi’s article no effort whatsoever is made to actually compare the war in Gaza with the “sheer inhumanity unfolding” in four out of the five alternatives he has bothered to mention: Iraq, Syria, Tigray, and Myanmar. Those four “moral calamities” are simply never mentioned again! He does try to formulate one argument for why the war in Gaza deserves the focus of our attention more than the war in Ukraine, but all he does is assert that since the war in Gaza is given more TV and social media coverage, it is also where our moral outrage should be directed. This, by the way, is what pscyhologists call “salience bias“: whatever captures our attention is mistakenly believed to be intrinsically more important. This is also sometimes called “shiny object syndrome“. I’ll have more on this in a future post.

I will in the very near future look in more detail at the “five reasons” that Bodhi provides for insisting that the war in Gaza, above all else, must be recognized as “the major moral calamity of our time.” But it must be emphasized that nowhere in these “five reasons” does he ever attempt to actually compare the war in Gaza with any other humanitarian crisis, with the already mentioned exception of the strange argument (truly bizarre, in fact, coming from a “senior American Buddhist monk”) that we should automatically judge the importance of world events based on what we see on TV and social media.

I will end below with my own list of 12 humanitarian crises that I think deserve our attention. But should we ask: do these other calamities deserve more attention than the war in Gaza? Do they deserve less? The same? No, we should not ask this question, in my opinion. I do not believe that it is possible to rank such horrors in order of their relative “gravities”. What grotesque unit of measurement could one use to accomplish such a task? One can look at body counts (and while sifting through the corpses we can try to distinguish civilians from soldiers, children from adults, women from men, guilty from “innocent”), the number of children who starve to death, the number of people displaced, the number of bombs dropped, the number of rapes, the number of hostages, the number of limbs lost, the number of people blinded, the buildings destroyed, the outbreaks of disease, the cumulative psychological trauma of those who manage to survive, etc. And we could try to combine all these blood soaked statistics to come up with some kind of objective metric of human suffering. And then we could calculate some sort of numerical “suffering score” for every tragedy, and place it in it’s properly ordered place in our Excel spreadsheet of horrors. But, surely, that way madness lies.

The Buddha taught us to not look away from suffering. This is the First Noble Truth. But he never taught us to treat one particular instance of suffering as somehow “the gravest” and more deserving of our attention than other suffering.

Finally, here is a list of other disasters (I will write more about each in the near future):

- The Congo Conflict

- The Syrian Civil War

- The Civil War in Sudan

- The War in Yemen

- The plight of the Kurdish people

- The Russian Invasion of Ukraine

- The Rise of Fascism in the United States

- World Hunger

- Tyranny in China

- The humanitarian crisis in Haiti

- Mass Incarceration in the United States

- The International Rise of Autocracy

The Tikvah Fund is offering a free online course taught by Einat Wilf: “Zionism and Anti-Zionism: The History of Two Opposing Ideas A new online course with Dr. Einat Wilf and Zoé Tara Zeigherman”.

The Tikvah Fund is offering a free online course taught by Einat Wilf: “Zionism and Anti-Zionism: The History of Two Opposing Ideas A new online course with Dr. Einat Wilf and Zoé Tara Zeigherman”.

The melancholy and disgraceful fact being established that, in these closing decades of the nineteenth century, the long-suffering Jew is still universally exposed to injustice, proportioned to the barbarity of the nation that surrounds him, from the indescribable atrocities of the Russian mobs, through every degree of refined insult to petty mortifications, the inevitable result has been to arouse most thinking Jews the necessity of a vigrous and concerted action of defense. They have long enough practiced to no purpose the doctrine which Christendom has been content to preach, and which was inculcated by one of their own race, when the right cheek was smitten to turn the left. They have proved themselves willing and able to assimilate with whatever people and endure every climatic influence. But blind intolerance and ignorance are now forcibly driving them into that position which they have so long hesitated to assume. They must establish an independent nationality …. I am fully persuaded that all suggested solutions other than this of the Jewish problem are but temporary palliatives.

The melancholy and disgraceful fact being established that, in these closing decades of the nineteenth century, the long-suffering Jew is still universally exposed to injustice, proportioned to the barbarity of the nation that surrounds him, from the indescribable atrocities of the Russian mobs, through every degree of refined insult to petty mortifications, the inevitable result has been to arouse most thinking Jews the necessity of a vigrous and concerted action of defense. They have long enough practiced to no purpose the doctrine which Christendom has been content to preach, and which was inculcated by one of their own race, when the right cheek was smitten to turn the left. They have proved themselves willing and able to assimilate with whatever people and endure every climatic influence. But blind intolerance and ignorance are now forcibly driving them into that position which they have so long hesitated to assume. They must establish an independent nationality …. I am fully persuaded that all suggested solutions other than this of the Jewish problem are but temporary palliatives. The name Emma Lazarus might not ring a bell, but you are certainly familiar with her work. She wrote the poem “The New Colossus”, which is engraved on the base of the Statue of Liberty. Lazarus published her first poetry collection when whe was just 18 years old (some of the poems had been written when she was just 14). In fact, Lazarus, who died in 1887 at the age of 38, would not live long enough to witness the the first World Zionist Congress, which took place in Basel, Switzerland, in August, 1897. That historic gathering was a direct result of the growing realization so clearly expressed by Lazarus that “all suggested solutions other than this [Zionism] of the Jewish problem are but temporary palliatives.”

The name Emma Lazarus might not ring a bell, but you are certainly familiar with her work. She wrote the poem “The New Colossus”, which is engraved on the base of the Statue of Liberty. Lazarus published her first poetry collection when whe was just 18 years old (some of the poems had been written when she was just 14). In fact, Lazarus, who died in 1887 at the age of 38, would not live long enough to witness the the first World Zionist Congress, which took place in Basel, Switzerland, in August, 1897. That historic gathering was a direct result of the growing realization so clearly expressed by Lazarus that “all suggested solutions other than this [Zionism] of the Jewish problem are but temporary palliatives.”

Also while still quite young I became a socialist. In high school my “activism” was limited to reading books and writing papers on subjects like Ho Chi Minh, the Haymarket Martyrs, and the Chinese Revolution. But when I went to college I finally found other like-minded leftists to work together with. I enthusiastically threw myself into the anti-apartheid movement, which had gained a lot of momentum thanks to the Soweto uprising and it’s brutal supression. I also worked for the ERA (remember the ERA??). I even got involved in labor solidarity (there was a strike by the Teamsters at a local Coca-Cola bottling plant). The list goes on.

Also while still quite young I became a socialist. In high school my “activism” was limited to reading books and writing papers on subjects like Ho Chi Minh, the Haymarket Martyrs, and the Chinese Revolution. But when I went to college I finally found other like-minded leftists to work together with. I enthusiastically threw myself into the anti-apartheid movement, which had gained a lot of momentum thanks to the Soweto uprising and it’s brutal supression. I also worked for the ERA (remember the ERA??). I even got involved in labor solidarity (there was a strike by the Teamsters at a local Coca-Cola bottling plant). The list goes on. After college I was able to graduate from labor solidarity to being an actual union member (in the Steelworkers and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, IBEW). I was very proud that my IBEW local passed a resolution calling for Martin Luther King’s birthday to be made a national holiday (this was back before it was). In this little bio I’m trying to stick to religion and politics, but I should mention that it was during these years that I met the love of my life, and to be honest I’m not at all sure how much the rest of this really matters compare to that. But life does not stop simply because one has found one’s true love. Quite the opposite.

After college I was able to graduate from labor solidarity to being an actual union member (in the Steelworkers and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, IBEW). I was very proud that my IBEW local passed a resolution calling for Martin Luther King’s birthday to be made a national holiday (this was back before it was). In this little bio I’m trying to stick to religion and politics, but I should mention that it was during these years that I met the love of my life, and to be honest I’m not at all sure how much the rest of this really matters compare to that. But life does not stop simply because one has found one’s true love. Quite the opposite. Now, where was I? Oh, eventually I went back to school and got my PhD in Theoretical Physical Chemistry (focussing on chaos theory and non-linear systems). And then I went on to do a post-doc in protein x-ray crystallography. I managed to stay involved in things like abortion rights, the anti-nuclear power movement, and opposition to the first Gulf War. Then one fine day it dawned on me that as part of my training and work as a scientist I had learned quite a lot about computers. I also learned that being a Unix System Adminstrator paid, easily, twice as much as being a post-doc. And at this time in human history, if you could spell “Unix” you could become a Unix System Administrator. So I followed the money.

Now, where was I? Oh, eventually I went back to school and got my PhD in Theoretical Physical Chemistry (focussing on chaos theory and non-linear systems). And then I went on to do a post-doc in protein x-ray crystallography. I managed to stay involved in things like abortion rights, the anti-nuclear power movement, and opposition to the first Gulf War. Then one fine day it dawned on me that as part of my training and work as a scientist I had learned quite a lot about computers. I also learned that being a Unix System Adminstrator paid, easily, twice as much as being a post-doc. And at this time in human history, if you could spell “Unix” you could become a Unix System Administrator. So I followed the money. From 2004 on I maintained my political sympathies, but focussed my energies on the Dharma. As a teacher I have tried to avoid misusing whatever little “authority” I might have to promote my own political beliefs. I am well aware of the fact that Buddhists come in all political flavors, and I consider it my responsibility to embrace all my fellow practitioners as friends in the Dharma, regardless of their political views, or lack thereof. I always cringe when other teachers make a point of promoting their own political agenda. Of course these teachers inevitably claim that their political agenda somehow isn’t really “political”, rather they insist that their favorite political causes are “moral” issues that are thereby, somehow, “above politics” or something like that. I consider that to be semantic quibbling, at best. Of course one’s political beliefs are based on one’s moral beliefs. Where else could political beliefs come from? But if one acts on the basis of one’s beliefs, then that action is, necessarily, political.

From 2004 on I maintained my political sympathies, but focussed my energies on the Dharma. As a teacher I have tried to avoid misusing whatever little “authority” I might have to promote my own political beliefs. I am well aware of the fact that Buddhists come in all political flavors, and I consider it my responsibility to embrace all my fellow practitioners as friends in the Dharma, regardless of their political views, or lack thereof. I always cringe when other teachers make a point of promoting their own political agenda. Of course these teachers inevitably claim that their political agenda somehow isn’t really “political”, rather they insist that their favorite political causes are “moral” issues that are thereby, somehow, “above politics” or something like that. I consider that to be semantic quibbling, at best. Of course one’s political beliefs are based on one’s moral beliefs. Where else could political beliefs come from? But if one acts on the basis of one’s beliefs, then that action is, necessarily, political. The same thing holds true for the claim that Israel is a “colonial settler state”, or that Israel is an “apartheid regime”. These are all political slogans, and very dubious ones at that. Not only are they political slogans, but they are the political slogans of the enemies of Israel: Hamas, Hezbollah, Iran, etc. I am not an enemy of Israel. In point of fact I strongly support Israel. I am a Zionist.

The same thing holds true for the claim that Israel is a “colonial settler state”, or that Israel is an “apartheid regime”. These are all political slogans, and very dubious ones at that. Not only are they political slogans, but they are the political slogans of the enemies of Israel: Hamas, Hezbollah, Iran, etc. I am not an enemy of Israel. In point of fact I strongly support Israel. I am a Zionist.