Once the Jewish state of Israel was established, one might suppose that there was no longer any need for Zionism. After all, hadn’t the goal of Zionism been accomplished? However, there still remained this one vital issue: would Israel survive?

In August of 1948, a young Syrian intellectual named Constantine Zurayk published a book titled Ma’na al-Nakba (معنى النكبة). The English title given to the book when it was translated 8 years later was The Meaning of the Disaster. When Zurayk’s book first appeared, the Israeli War of Independence (aka, “the first Arab-Israeli War”) was not yet over, but it was already clear who would win. The only question was: how total would Israel’s victory be? Put another way, how complete would the Arabs’ disaster/nakba be?

Here is how Zurayk characterized the “disaster in every sense of the word” even while it was still unfolding before the world’s eyes:

The defeat of the Arabs in Palestine is no simple setback or light, passing evil. It is a disaster in every sense of the word and one of the harshest of the trials and tribulations with which the Arabs have been afflicted throughout their long history—a history marked by numerous trials and tribulations.

Seven Arab states declare war on Zionism in Palestine, stop impotent before it, and then turn on their heels. The representatives of the Arabs deliver fiery speeches in the highest international forums, warning what the Arab states and peoples will do if this or that decision be enacted. Declarations fall like bombs from the mouths of officials at the meetings of the Arab League, but when action becomes necessary, the fire is still and quiet, the steel and iron are rusted and twisted, quick to bend and disintegrate. The bombs are hollow and empty. They cause no damage and kill no one.

Seven states seek the abolition of partition and the subduing of Zionism, but they leave the battle having lost a not inconsiderable portion of the soil of Palestine, even of the part “given” to the Arabs in the partition. They are forced to accept a truce in which there is neither advantage nor gain for them. [p. 2]

If this isn’t quite clear enough, Zurayk is good enough to elaborate further a few pages later:

When we view this disaster and appraise its extent and its results, it is also right and fair for us to know that it is only one battle in a long war. If we have lost this battle, that does not mean that we have lost the whole war or that we have been finally routed with no possibility of a later revival.

This battle is decisive from numerous points of view, for on it depends the establishment or extinction of the Zionist state. If we lose the battle completely, and the Zionist state is established, the Jews of the whole world will no doubt muster all their strength to preserve, reinforce, and expand it, as they mustered their strength to found it. [p. 7]

Zurayk makes it clear that the humliating defeat of the Arabs must be quickly followed by decisive action by a newly unified Arab popular struggle, even if the final goal of Israel’s destruction might take longer. Otherwise history will judge the Arabs (unjustly, Zurayk protests) only on the basis of the “disaster”:

It will also be said that the Arabs of Palestine have proved themselves weak and impotent; that no sooner had the first bombs fallen than they fled in utter rout, evacuated their cities and their strongholds, and surrendered them to the enemy on a silver platter, that a large number of them had fled even before the battle and had taken refuge in the other Arab countries and in remote regions of Palestine.

I do not deny that cowardice and disintegration have appeared among the Arabs, in Palestine and elsewhere. [p. 26]

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2737764/Palestinian-leader-say-Hamas-caused-prolonged-war.html

Zurayk’s hope was that the Arabs could rally, and that the “trials and tribulations” that the Arab world was undergoing (that is, the birth of the state of Israel) would yet prove to be a catalyst for a new awakening of Arab nationalism. In Zurayk’s opinion this would only be the case if the Arab people learned the necessary lesson from the “disaster”.

Zurayk was not ambiguous about what he thought the necessary lesson to be:

The present struggle, which we have described and whose principles and conditions we have drawn up, is necessary for the battle we are now waging. However, the war waged to uproot Zionism and to conquer it completely will not be finished in a single battle. On the contrary it will require a long and protracted war. [p. 34]

Zurayk makes it clear that there can be only one “Fundamental Solution”, as he calls it, to the problem of the Nakba: the complete destruction of Israel. But he is at pains to assure us that he has reason, morality, and even international law on his side. The Arab cause, in Zurayk’s view, is based on “principle”. Zurayk acknowledges that the Zionists also claim to have a “principled” cause as well, however: “They [the Zionists] do indeed flaunt many ‘principles’, but none of these stand before fact and evidence,” he claims (p. 60). Therefore it is not just Arabs who should join in the “crusade” (a term Zurayk frequently uses) against Israel, but all of humanity should join together to support the “lofty human ideal” of Israel’s destruction:

We deduce from all that has preceded that the struggle against Zionism and against the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine is not, from the Arab point of view, merely a national struggle, but a struggle for the sake of a lofty human ideal—a struggle between right and might, between principle and interest. [p. 59]

Zurayk insists that “religious tolerance” is among the “ideals” and “principles” that he champions (p. 72), and he certainly would have been horrified at any suggestion that he could conceivably be antisemitic. And yet his little book drips with classical antisemitic tropes:

Zionism does not only consist of those groups and colonies scattered in Palestine; it is a worldwide net, well prepared scientifically and financially, which dominates the influential countries of the world, and which has dedicated all its strength to the realization of its goal, namely building a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine.

It is, therefore, our duty to acknowledge the terrifying strength which the enemy possesses and to take it into account when we view our present problem and try to remedy it. [p. 5]

Later on, Zurayk provides the reader with a master-class in classic antisemitism when he opines on the “world-wide power of the Jews — politically, financially, and culturally.”

This power became clear during the first World War. It extracted the Balfour Declaration from the British government, then imposed on the members of the League of Nations the inclusion of this declaration in the text of the mandate, and continued under the mandate to act in England and America so as to secure continued support for its aggressive policy, despite the awakening of British politicians to its dangers and despite successive Arab revolts. In recent years this power has been centered in the United States. No one who has not stayed in that country and studied its conditions can truly estimate the extent of this power or visualize the aweful danger of it. Many American industries and financial institutions are in the hands of Jews, not to mention the press, radio, cinema, and other media of propaganda, or Jewish voters in the states of New York, Illinois, Ohio, and others which are important in presidential elections, especially in these days when the conflict between Democrats and Republicans is at a peak and both parties are trying to acquire votes from any quarter possible. [pp. 65-66]

Just as Zurayk had hoped, out of the catastrophic failure, the Nakba, of 1947 to 1949, a renewed spirit of nationalism was kindled among the Arab masses. And Zurayk himself had more than a little to do with this nationalist awakening. And just as Zurayk had hoped, after 1948 Arab nationalism would become synonymous with hatred for Israel and with an obsessive fixation on its destruction. And over the decades the “Nakba” has even become a badge of honor, a slogan shouted at demonstrations. One might even be tempted to compare the Nakba to the Alamo. But such a comparison must be rejected due to the fact that the defenders of the Alamo chose to fight to the death rather than flee or surrender.

The melancholy and disgraceful fact being established that, in these closing decades of the nineteenth century, the long-suffering Jew is still universally exposed to injustice, proportioned to the barbarity of the nation that surrounds him, from the indescribable atrocities of the Russian mobs, through every degree of refined insult to petty mortifications, the inevitable result has been to arouse most thinking Jews the necessity of a vigrous and concerted action of defense. They have long enough practiced to no purpose the doctrine which Christendom has been content to preach, and which was inculcated by one of their own race, when the right cheek was smitten to turn the left. They have proved themselves willing and able to assimilate with whatever people and endure every climatic influence. But blind intolerance and ignorance are now forcibly driving them into that position which they have so long hesitated to assume. They must establish an independent nationality …. I am fully persuaded that all suggested solutions other than this of the Jewish problem are but temporary palliatives.

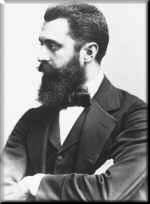

The melancholy and disgraceful fact being established that, in these closing decades of the nineteenth century, the long-suffering Jew is still universally exposed to injustice, proportioned to the barbarity of the nation that surrounds him, from the indescribable atrocities of the Russian mobs, through every degree of refined insult to petty mortifications, the inevitable result has been to arouse most thinking Jews the necessity of a vigrous and concerted action of defense. They have long enough practiced to no purpose the doctrine which Christendom has been content to preach, and which was inculcated by one of their own race, when the right cheek was smitten to turn the left. They have proved themselves willing and able to assimilate with whatever people and endure every climatic influence. But blind intolerance and ignorance are now forcibly driving them into that position which they have so long hesitated to assume. They must establish an independent nationality …. I am fully persuaded that all suggested solutions other than this of the Jewish problem are but temporary palliatives. The name Emma Lazarus might not ring a bell, but you are certainly familiar with her work. She wrote the poem “The New Colossus”, which is engraved on the base of the Statue of Liberty. Lazarus published her first poetry collection when whe was just 18 years old (some of the poems had been written when she was just 14). In fact, Lazarus, who died in 1887 at the age of 38, would not live long enough to witness the the first World Zionist Congress, which took place in Basel, Switzerland, in August, 1897. That historic gathering was a direct result of the growing realization so clearly expressed by Lazarus that “all suggested solutions other than this [Zionism] of the Jewish problem are but temporary palliatives.”

The name Emma Lazarus might not ring a bell, but you are certainly familiar with her work. She wrote the poem “The New Colossus”, which is engraved on the base of the Statue of Liberty. Lazarus published her first poetry collection when whe was just 18 years old (some of the poems had been written when she was just 14). In fact, Lazarus, who died in 1887 at the age of 38, would not live long enough to witness the the first World Zionist Congress, which took place in Basel, Switzerland, in August, 1897. That historic gathering was a direct result of the growing realization so clearly expressed by Lazarus that “all suggested solutions other than this [Zionism] of the Jewish problem are but temporary palliatives.”